How deferential is the Roberts court to presidential power?

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

Much recent commentary has suggested that the Roberts court is overly deferential to executive power – especially under President Donald Trump. The Niskanen Center, for example, contends that the court “is enabling Trump’s executive authority,” while the Brennan Center argues that the court has given “the president the power of a king.” But is this narrative supported by the empirical record? At the very least, is the Roberts court more deferential to presidential power than past courts? Our preliminary answer, like much else having to do with this court, is that it’s complicated.

What we looked at

The Supreme Court’s treatment of cases involving the presidency has long interested scholars of separation of powers. Indeed, research shows that justices who were appointed by the current president tend to favor that executive at higher rates than other justices. Other work examines how the court responds to perceived presidential overreach, finding that institutional constraints on executive power vary with the court’s composition.

This is in line with what is known as the attitudinal model, which suggests that judicial behavior reflects ideological preferences rather than neutral legal reasoning; in other words, that justices vote in favor of presidents with whose political ideology they agree. Along those lines, recent empirical work has demonstrated that partisan polarization affects judicial decision-making, with the justices increasingly dividing along party lines in politically salient cases.

This analysis builds on these foundations by examining support for the United States as a party on the merits docket. Support rates are calculated as the percentage of votes cast in favor of the United States’ position based on underlying data from the Supreme Court Database. Specifically, the analysis examines these rates across chief justice eras, by the political party of the appointing president, and by individual justices through the end of the 2024-2025 term.

Historical patterns: the long view

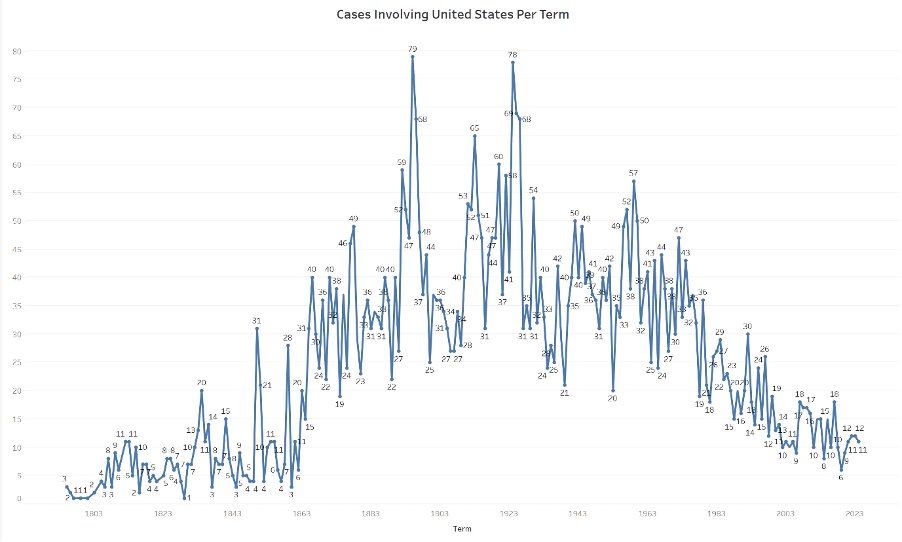

Figure 1, below, shows the number of cases involving the United States per term from 1803 through 2024. The pattern reveals dramatic growth through the early 20th century, peaking at 79 cases in the 1891 term during the court of Chief Justice Melville Fuller (1888-1910). This expansion reflected the growing reach of federal power and the court’s expanding docket. The mid-20th century saw continued high volumes, with the court of Chief Justice Earl Warren (1953-1969) often having over 40 such cases per term. Since the early 1980s, however, the overall number of cases has declined substantially as the court has reduced its total docket, although cases involving the United States remain a significant portion of the court’s work.

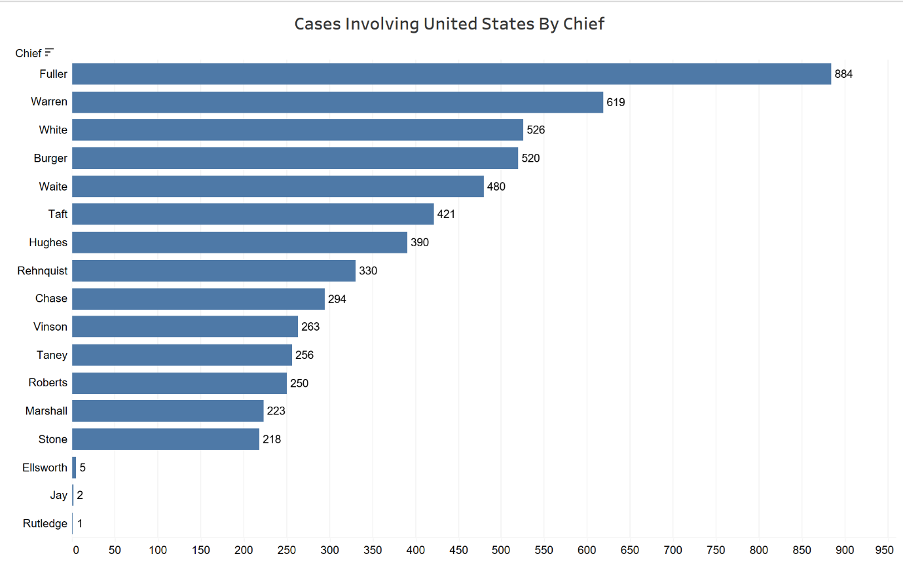

Figure 2, below, displays the total number of cases involving the United States by chief justice. Fuller’s dominance reflects both his relatively long tenure (of over two decades) and, again, the explosion of federal litigation in the late 19th century. The Warren court comes second with 619 cases, followed by the court of Chief Justice Edward Douglass White (1910-1921) with 526. Among recent chief justices, William Rehnquist (1986-2005) presided over 330 cases while John Roberts has seen 250 such cases through the 2024 term. As noted above, however, the Roberts court’s lower count likely reflects the court’s generally smaller docket rather than any reduced federal government presence.

Support for the United States by chief justice era

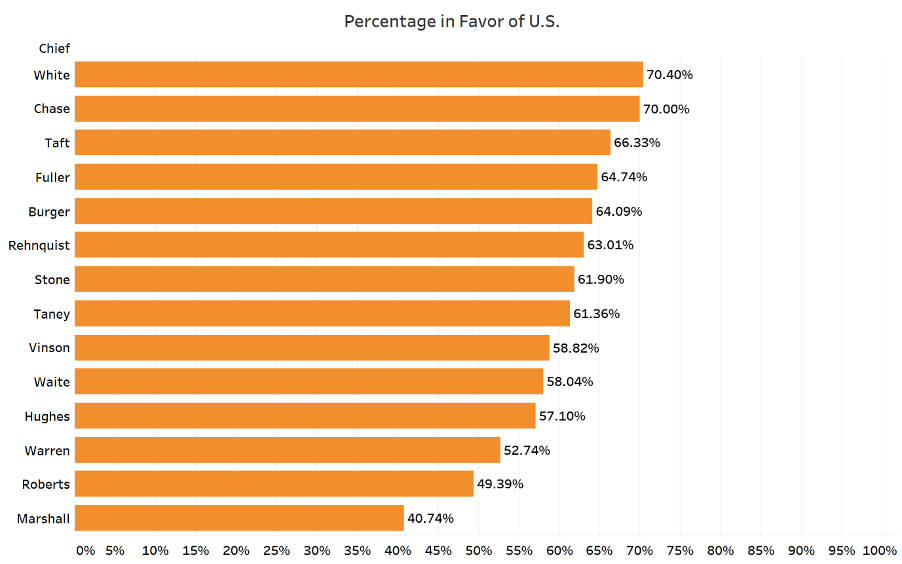

The next figure presents support rates for the United States across chief justice eras. The modern pattern shows considerable variation. The courts of White and Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase (1864-1873) led with 70.4% and 70% support for the United States, respectively, followed by the court of Chief Justice William Howard Taft (1921-1930), himself a former president, at 66.33%. Fuller, despite deciding the most cases, supported the government at 64.74%. Among more recent courts, that of Warren E. Burger (1969-1986) supported the United States 64.09% of the time, while Rehnquist’s was at 63.01%.

The famously liberal Warren court is notable for its 52.74% support rate – among the lowest of any chief justice era. This makes some sense: this relatively low rate came during a period of significant expansion in individual rights and skepticism toward government power. The Roberts court falls even nearer the bottom, however, at 49.39%.

Finally is the court under Chief Justice John Marshall (1801-1835). Given Marshall was generally considered a proponent of federal power, it is of some surprise that his court shows a historically low 40.74% support rate for the United States. That said, this may reflect the limited scope of federal authority in the early republic and the nascent state of executive power during that era more than anything else.

The partisan dimension

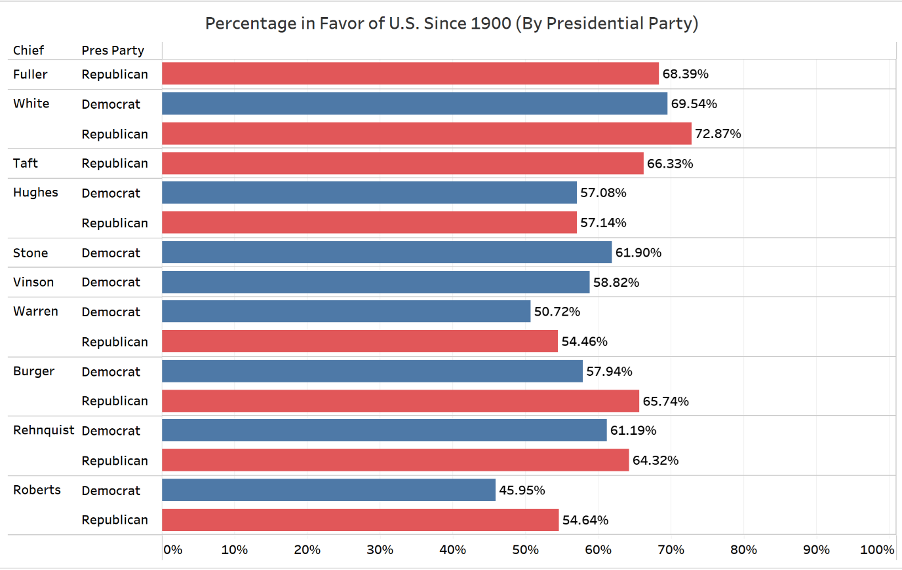

The next chart breaks down support for the United States by chief justice and the party of the president. The analysis is limited to chief justices since 1900 in order to focus on the modern era of more developed executive power.

When one party held a durable edge in appointments, the court’s support for the United States tended to be higher. For example, in the early 1900s (the Fuller, White, and Taft courts), the bulk of the justices were Republican appointees, reflecting that party’s dominance of the presidency for long stretches around the turn of the century. It’s thus unsurprising that the court frequently voted in favor of the Republican administration during this period. What’s more striking is how high the U.S. win rate was under Democratic administrations even with a Republican-appointed bench, such as in the White court era – an indicator that, during this period, the court’s general receptiveness to federal power often outweighed any simple party alignment.

These percentages decreased during the court of Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes (1930-1941). This era began with a bench still heavily shaped by earlier Republican administrations, but which rapidly became a Roosevelt-appointed court after the late 1930s (and FDR’s successive terms). By the time of the courts of Chief Justices Harlan Fiske Stone (1941-1946) and Fred M. Vinson (1946-1953), the story is more straightforward: the overwhelming majority of the justices were Democratic appointees (almost all entirely appointed by FDR, in Stone’s case), during Democratic terms.

That brings us to the Warren era. Although the Warren court is remembered as liberal, its roster was mixed – containing many Roosevelt/Truman appointees, but then supplemented by Republican Eisenhower appointees (including Warren himself) alongside later Kennedy/Johnson picks.

For the Burger and Rehnquist courts, the figure shows a clearer correlation between the party of the appointing president and the court’s support for the presidency than is present in the early-mid century: Both eras feature higher pro–U.S. rates under Republican administrations than Democratic ones. That pattern is broadly consistent with the reality that, over the long run of each court, Republican appointees held a durable edge in the voting coalitions that most often formed majorities. But the gap is also modest, especially under Rehnquist, where even a court with a Republican-appointed tilt still delivered substantial executive wins under Democratic presidents.

By the time Roberts became chief, the partisan structure is clearest. The bulk of the court is Republican-appointed and has been so since Roberts’ appointment as chief justice. There, a noticeably higher win rate for the United States under Republican administrations is consistent with the conventional wisdom about a Republican-appointed majority court.

Stepping back, the trend looks like a shift from weak partisan sorting to stronger partisan sorting over time. In the early 1900s and much of the mid-century, appointing-party composition helps explain some variation, but high United States win rates under both parties point to a court whose baseline posture toward federal power often dominated partisan alignment. Over time – especially by the late 20th century and then more sharply in the Roberts era – the relationship between the party of the appointing president and differential success for Republican versus Democratic administrations becomes more pronounced. The most plausible interpretation is that the docket and the parties’ legal agendas became more ideologically sorted: Modern Democratic and Republican administrations more often defend positions that map onto the court’s ideological cleavage, so the appointing-party composition has come to increasingly predict which administration will fare better in contested, high-salience government cases.

Individual justices and the current Roberts court

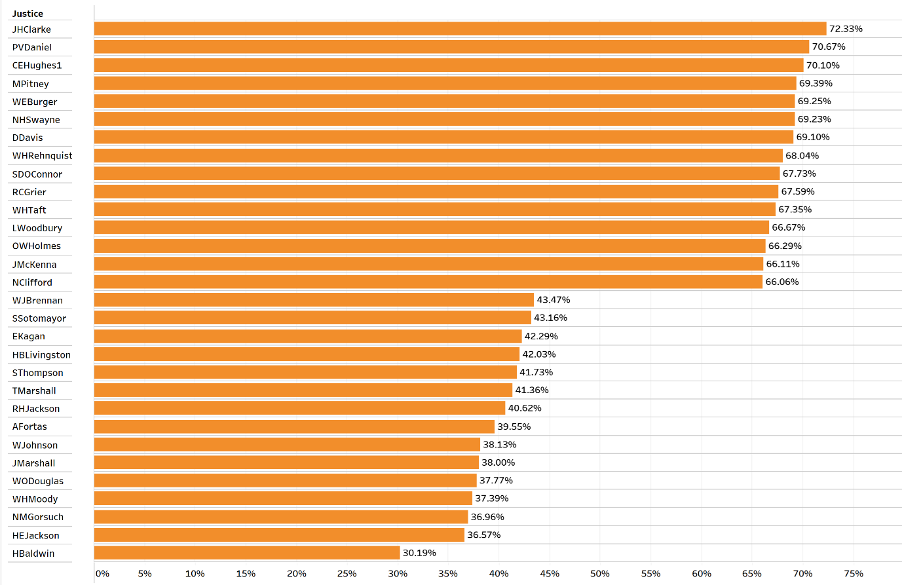

The voting patterns of current Roberts court justices deserve closer examination given contemporary debates about executive power. The following figure shows the overall top and bottom 15 justices by their support rate for the United States among those with at least 25 votes in such cases.

Among the current justices, none appear in the top 15. At the bottom there is a mix of the court’s conservative and liberal wings. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, often viewed as part of the court’s liberal wing, voted for the government 43.16% of the time. This places her just a touch above fellow liberal Justice Elena Kagan, who voted in favor of the government 42.29% of the time and significantly ahead of Justice Neil Gorsuch, one of the more conservative justices, who supported the government’s position less than 37% of the time, perhaps in line with his libertarian instincts. (The average support for the government across all justices with 25 or more votes was 55.82%.)

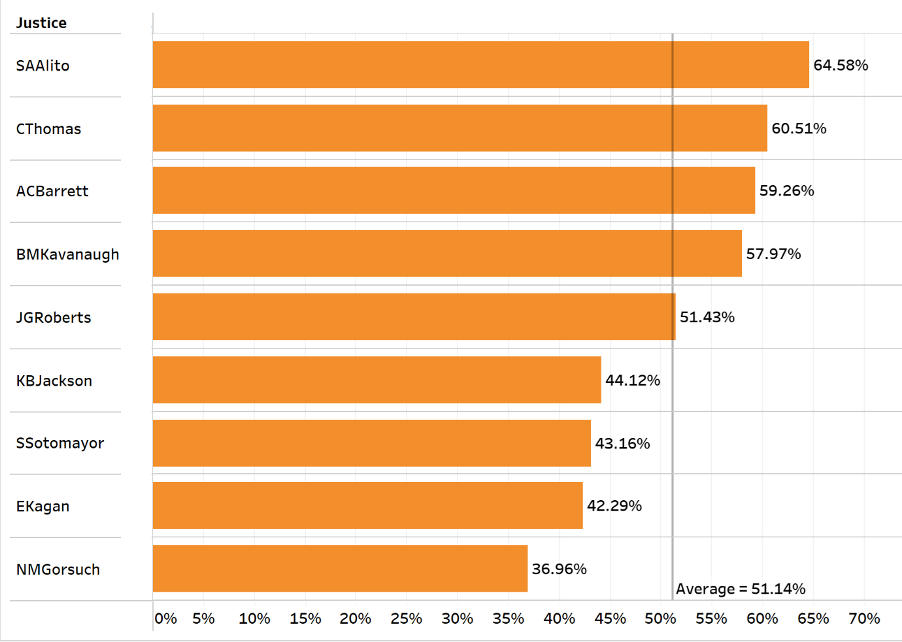

Further focusing on the current justices we see the following:

With the exception of Gorsuch, the conservative justices, led by Justice Samuel Alito, provide the highest support for the government. Roberts is right in the middle at 51.43%.

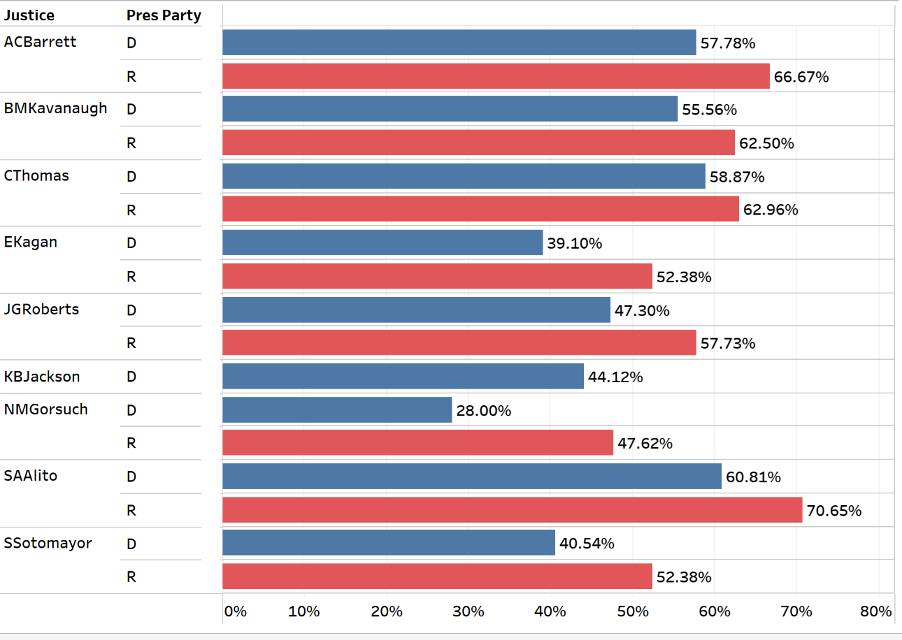

Moving to support for Republican versus Democratic administrations, across the Roberts court every justice shown is more likely to vote for the United States when a Republican administration is in office, though the size of that gap varies, as demonstrated by the chart above. The largest partisan swings appear for Kagan (a Democratic appointee with a relatively low pro-United States rate under Democratic administrations but, interestingly, a much higher rate under Republican ones) and Gorsuch (a Republican appointee whose pro-United States rate jumps sharply under Republican administrations). Roberts and Sotomayor also show sizable gaps favoring Republican administrations.

At the same time, the chart underscores that party alignment isn’t a complete explanation. Alito, who is a Republican appointee and considered strongly conservative, is highly pro-United States under both parties, just markedly more so under Republican administrations – consistent with a justice who is broadly receptive to government authority or law enforcement positions but especially aligned with conservative stances. The votes of Justices Amy Coney Barrett, Brett Kavanaugh, and Clarence Thomas, also all Republican appointees, reflect a baseline willingness to side with the government but less so than Alito. (Jackson, a Democratic appointee, appears only under Democratic administrations here.) While the pattern may fit conventional expectations for a court with a durable Republican-appointed majority in which Republican administrations benefit more often, the magnitude depends on each justice’s jurisprudential commitments and the ideological content of the government’s positions in the cases that actually reach the merits docket.

So what does this tell us?

The data present a more nuanced picture than recent commentary might suggest, and especially those who contend that the Roberts court is overly deferential to executive power. Indeed, this court’s 49.39% support rate for the United States is below the historical average and substantially lower than the courts led by Fuller, Taft, Warren, Burger, and Rehnquist – that is, all the courts since 1900.

The partisan analysis also reveals some interesting patterns. Republican-appointed courts since 1900 have generally supported the government at higher rates during Republican presidencies, though the Roberts court shows lower overall support rates than its predecessors regardless of which party controls the White House. This could reflect polarization in case selection, with more controversial executive actions reaching the court, or genuine changes in judicial philosophy about executive power.

That said, several important limitations must be acknowledged. First, and perhaps most significantly, this analysis excludes the shadow docket. Emergency applications and stays have become increasingly important in recent years, particularly for cases involving significant issues relating to immigration, pandemic response, and other executive actions. The shadow docket may tell a separate story about deference to executive power, and analyzing it requires accounting for different legal standards and procedural postures.

Second, we have excluded cases involving agency deference where the United States was not directly a party. We have also not examined cases where the president or a cabinet member’s name is in the case caption instead of the United States (such as those over presidential immunity) or where other government officials may be a named party. I plan to do so in a follow-up study.

Third, the analysis does not distinguish between Trump’s two presidencies. During Trump’s first term, the Roberts court decided numerous cases involving his administration. The current term remains in its early stages with limited data. Separating these periods might well reveal different patterns.

Fourth, the analysis treats all cases involving the United States equally, without accounting for issue area, case importance, or the strength of the government’s legal position. Criminal cases, civil litigation, and constitutional challenges might present different voting patterns, and a more granular analysis could reveal that the court is deferential in some domains but not others (and might also help explain why even certain Democratic-appointed justices favor the United States in Republican versus Democratic administrations – something quite notable but beyond the scope of the current article).

Finally, examining whether support is Trump-specific or party-specific requires additional work. The clustering of current justices around similar support rates suggests that partisan differences may be less pronounced than in earlier eras, but this could also reflect the types of cases reaching the court or the strength of legal arguments presented. Additionally, since the sample size for the current court composition is still relatively low, comparisons between this court and previous eras will become clearer as the justices work through more cases.

The bottom line

Despite claims to the contrary, the Roberts court, rather than showing exceptional deference to executive power, actually falls below the historical average in its support for the federal government when it appears as a party on the merits docket.

But perhaps what most emerges from a historical analysis is a complex picture that resists simple narratives. The court’s relationship with executive power varies across eras, reflects changing understandings of federal authority, and appears influenced by both partisan considerations and broader jurisprudential trends. At the very least, this initial analysis provides a foundation for deeper examination of these patterns and their implications for the separation of powers in these politically fraught times.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns