The long and short of Supreme Court oral arguments

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

When Daniel Webster stood before the Supreme Court in 1824 to argue Gibbons v. Ogden, over the court’s power to regulate interstate commerce, he spoke for hours across multiple days. In the landmark 1819 case of McCulloch v. Maryland, the oral arguments stretched for four days. The Dartmouth College case, which was argued a year before and delved deep into the Constitution’s contracts clause, consumed three full days of the court’s time. As former U.S. Solicitor General Seth Waxman once observed, “no advocate today will ever have the opportunity to perform in the arena [advocates such as] Webster commanded.”

Indeed, the modern Supreme Court operates in a drastically different world. On Nov. 4, 2025, the court heard oral argument in Coney Island Auto Parts Unlimited, Inc. v. Burton for just 35 minutes and 42 seconds – leading Josh Blackman of The Volokh Conspiracy to ask if this was “the shortest SCOTUS oral argument in the modern era.”

This article examines how oral argument time has evolved at the Supreme Court over nearly seven decades, using data from Oyez (procured with the help of Jack Truscott) covering the period from the 1955-56 term through the current one. What emerges is the story of a precipitous decline in total argument time since the 1960s, followed by a recent uptick in average argument length per case as the court’s docket has shrunk.

The decline in total argument hours

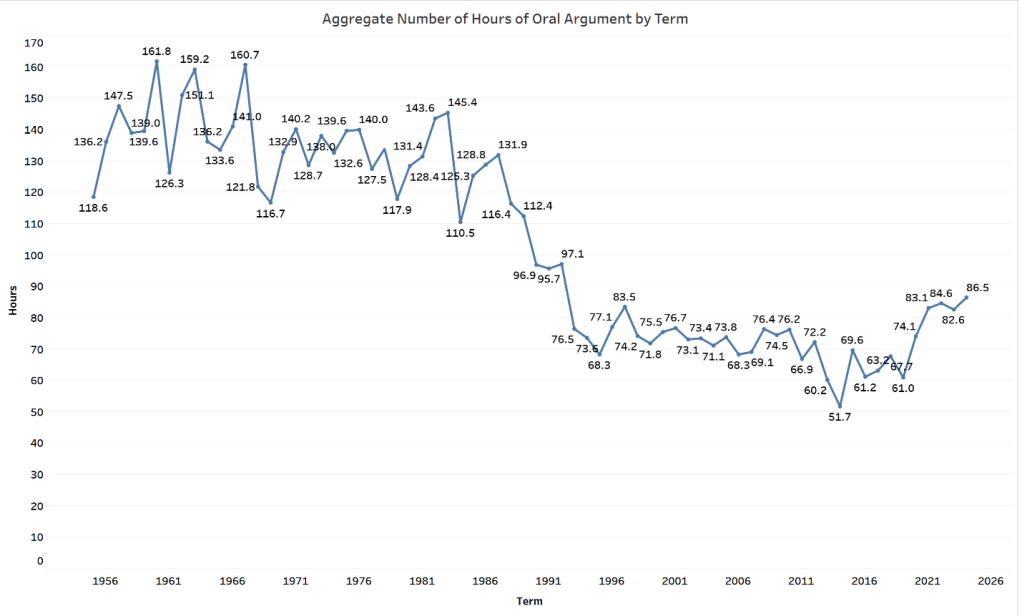

The most striking trend appears in the aggregate number of hours the court devotes to oral arguments each term. During the Warren court era of the late 1950s and 1960s, the court routinely heard more than 140 hours of oral argument per term, with peaks reaching 161.8 hours in 1961 and 160.7 hours in 1967. These were marathon argument sessions, reflecting both the court’s heavy caseload and the traditional practice of granting extended time for argument.

The picture changed dramatically beginning in the late 1980s and early 1990s. By the 1992-93 term, total argument time had plummeted to 97.1 hours. The decline continued through the early 2000s, bottoming out at 51.7 hours in the 2013-14 term – a reduction of nearly 70% from the highs in the 1960s. The most recent complete terms have seen a modest recovery, with the 2024-25 term recording 86.5 hours of oral argument, but this remains far below the court’s historical practice.

This trend line reflects the court’s evolution from a court that heard argument in hundreds of cases per term to one with a much smaller docket. In the 1960s and 1970s, the court regularly heard argument in 150 or more cases per term. Today, that number typically hovers between 60 and 70 cases. The court is no longer functioning as a general error-correction court, as it once did – hearing cases of even middling impact – but instead acting as an institution selecting cases of exceptional importance. (And while the justices still take up a slew of statutory cases each term where they often aim to resolve circuit splits, these do not generate nearly as much heated discussion and debate.)

The recent rise in average argument length

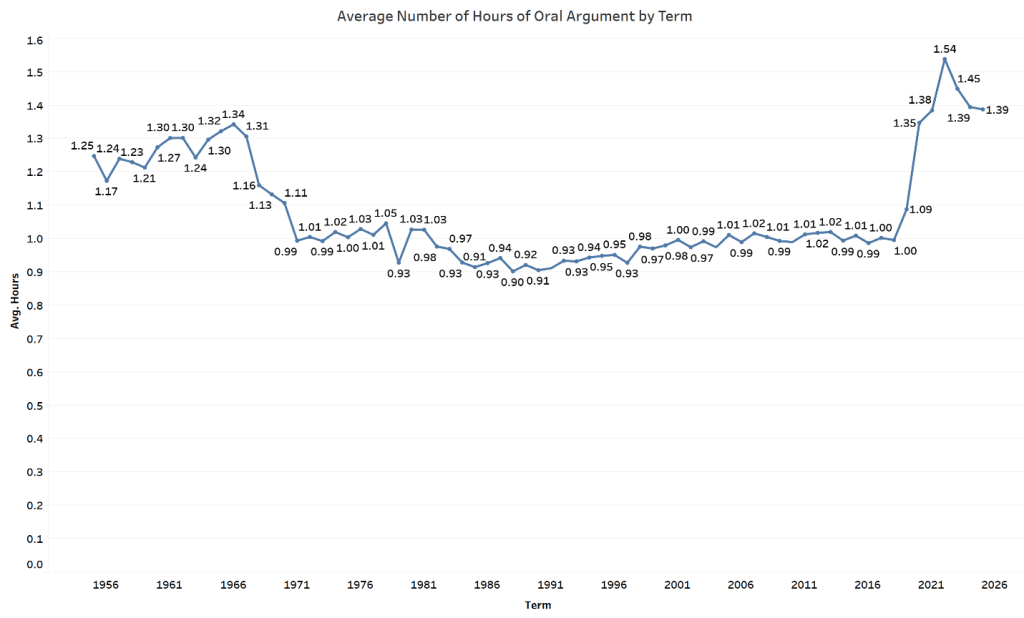

While total argument time has plummeted, a perhaps counterintuitive trend has emerged in average argument length per case. After declining from the late 1960s through the late 1980s and early 1990s – when the average time per argument hovered around 0.90 to 0.95 hours (roughly 54-57 minutes) – the past decade has actually seen average argument times creep upward.

This began with the Covid pandemic in 2020, in which the court introduced ordered participation during remote arguments, and which has remained in hybrid form to this day. The 2022-23 term marked a notable turning point, with the average oral argument lasting 1.54 hours (92.4 minutes) – the highest in this set. And the 2024-25 term came close at 1.45 hours (87 minutes).

This increase in per-case argument time appears to reflect the court’s strategic use of its scarcer argument slots. With fewer cases granted review, the justices can afford to spend more time exploring the issues in each individual case. High-profile cases in recent years have thus featured extended arguments: For example, the court spent over five hours deliberating in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, which involved very similar but not identical claims and were argued separately, while Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization was allotted 70 minutes for oral argument but lasted nearly two hours.

The trend also reflects changes in how the justices approach oral argument. The modern court is highly active during arguments, with justices interrupting advocates frequently to probe the implications of their positions. This stands in stark contrast to Webster’s era, or even the mid-20th-century practice, when advocates could expect to deliver sustained presentations with minimal judicial intervention.

The shortest arguments

The briefest arguments reveal how the court handles cases where little remains to be said. Carella v. California, argued on April 26, 1989, holds the record for the shortest argument at just 24 minutes and 32 seconds. The case centered on whether California’s statutory presumptions in a grand theft prosecution violated due process.

What made the argument so brief? California confessed error from the get-go. Deputy District Attorney Arnold Guminski opened by acknowledging that “little did we anticipate that this case, which resulted in an unpublished opinion without precedential value, would’ve come before this Court.” With constitutional error admitted, the argument devolved into a narrow discussion of harmless error – whether the case should be remanded (sent back to a lower court) or the court could decide the issue itself.

The second shortest argument, Hardin v. Straub, was argued on March 22, 1989, ran 27 minutes, and presented an even more technical question: whether Michigan’s prisoner tolling statute applied to Section 1983 claims in federal court. The argument was abstract and doctrinal – no factual disputes, no constitutional dimensions, just a straightforward question of which procedural rules applied. The argument ended after both sides had made their statutory interpretation points, with nothing more to say.

As noted above, this term’s Coney Island Auto Parts Unlimited v. Burton lasted only 35 minutes and 42 seconds. This bankruptcy case asked whether Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(c)(1)’s “reasonable time” requirement applies to motions challenging void judgments. Early on, Coney Island Auto Parts abandoned any argument that the motion at issue was actually timely, and having reserved no alternative ground for relief, the argument largely consisted of the court testing the logical boundaries of a categorical rule rather than focusing on the intricacies of any position from either side.

These brief arguments share key features: confession of error, highly technical procedural questions, or abandonment of alternative arguments that might have required more extensive discussion. When there’s little left to argue about, the court sees little reason to prolong the exercise.

The longest arguments

Extended arguments remain reserved for cases of exceptional complexity. The Penn Central Merger and N & W Inclusion Cases from 1967 ran 3 hours and 56 minutes, reflecting a massive railroad consolidation and affecting many commercial and individual interests.

More recently, in Haaland v. Brackeen, on Nov. 9, 2022, the justices heard 3 hours, 12 minutes, and 20 seconds of argument across four consolidated cases. The case challenged the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act under Article I of the Constitution and on equal protection grounds. The extraordinary time devoted to the case (for which the court had originally allocated 100 minutes) reflected not just the consolidation of multiple cases, but the profound complexity of the issues: the scope of Congress’ Indian commerce clause power, the distinction between political and racial classifications, the intersection of federal Indian law with state family law, and the proper framework for analyzing ICWA’s placement preferences. The three-hour argument barely sufficed.

Where we’re headed?

The data tell a story of institutional evolution. From the 160-hour terms of the 1960s to the 50-hour trough of the 2010s, then back up toward 85 hours today – these shifts track the court’s transformation from error-correction tribunal to constitutional court. But perhaps the more revealing metric is average time per case: up from the low-to-mid 50 minutes of the 1990s to over 90 minutes today.

This reflects a deliberate choice to invest more resources per case. The court could maintain hour-long arguments and simply hear fewer cases; instead, it’s lengthening arguments even as the docket shrinks. This suggests that the justices may find extended engagement valuable – not just to educate themselves but to test theories, probe implications, and develop the law through dialogue.

The brief arguments also show the system’s efficiency: when cases are simple or parties concede key points, the court dispenses with formality and moves on. The extended arguments demonstrate commitment: where cases are genuinely complex or momentous, the court makes time. Haaland, for example, required three hours not because the parties rambled but because different advocates needed to address genuinely difficult questions about federalism, equal protection, and the scope of congressional power over tribes.

Looking forward, expect the trend or at least stabilization towards longer per-case arguments to continue. As the court’s docket stabilizes around 60-70 cases per term – down from 150+ decades ago – the justices can afford to grant extended time in truly complex cases. We may see more frequent two-hour or three-hour arguments in cases involving multiple consolidated parties or particularly novel constitutional questions. And ultra-brief arguments will persist as outliers. Cases like Coney Island, Carella, and Hardin demonstrate that when there’s nothing left to argue, even the Supreme Court doesn’t waste time.

Perhaps even clearer is that Daniel Webster’s multi-day orations belong to history. Today’s court has calibrated oral argument to serve as an intensive stress-test of legal positions – sometimes requiring hours, sometimes mere minutes, but generally matching time to (perceived) necessity. In an era when the court chooses its cases carefully, it can afford to argue each one thoroughly. That’s not a diminution of the importance of oral argument, but rather its refinement as a tool for the most consequential legal questions.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns

Cases: Coney Island Auto Parts Unlimited, Inc. v. Burton